This is a guest post from our research collaborator: Alfredo Conde is a Research Assistant with the Community University Partnership at the University of Alberta School of Public Health, in his role he works closely with EndPovertyEdmonton. He has a Masters degree in Development Economics.

Though we don't have population level statistics post-pandemic, poverty in Canada had been steadily declining over the last few years. This is thanks in part to the government's expanded social support programs. Published in 2018, Opportunity for All is Canada's first official poverty elimination strategy that made the Market Basket Measure (MBM) Canada's official poverty measure. The strategy sets an ambitious target to reduce poverty by 20% by 2020 and 50% by 2030. Through investments into the economic well-being of the middle class, Canada's poverty targets appear to be on the right track. However, there is an overlooked group in Canada's workforce in need of consideration—the working poor.

An Untapped Opportunity for Economic Growth

Canada's Market Basket Measure

The MBM describes the poverty line based on the cost of a basket of food, clothing, shelter, transportation, and other items representing a modest, basic standard of living. The poverty line is relative to the size of the family and it's location, since cost of living varies across the country.

In 2019, the poverty line for a family of 4 living in the Edmonton area was $47,967 after tax. For a single it was $23,983.

Source: Stats Canada

Representing approximately 30% of working-age people in poverty in 2017, the working poor are an untapped opportunity for economic growth. Working poverty can be experienced by anyone and there are many similarities between people who are and are not experiencing working poverty. The data indicates that working poverty results from the cracks within Canada's economic and labour market system, rather than personal failure.

So, who are the working poor? For our research, we adapted a definition used by Fleury and Fortin in their 2006 report on the working poor: a situation in which an individual works at least 910 hours a year (or 17.5 hours/ week), but whose household income falls below the poverty line. Research on the working poor is typically limited to people aged 18-64 and excludes students. However, we included anyone aged 16+ in our analysis to consider the struggles faced by students in poverty and those in old age poverty.

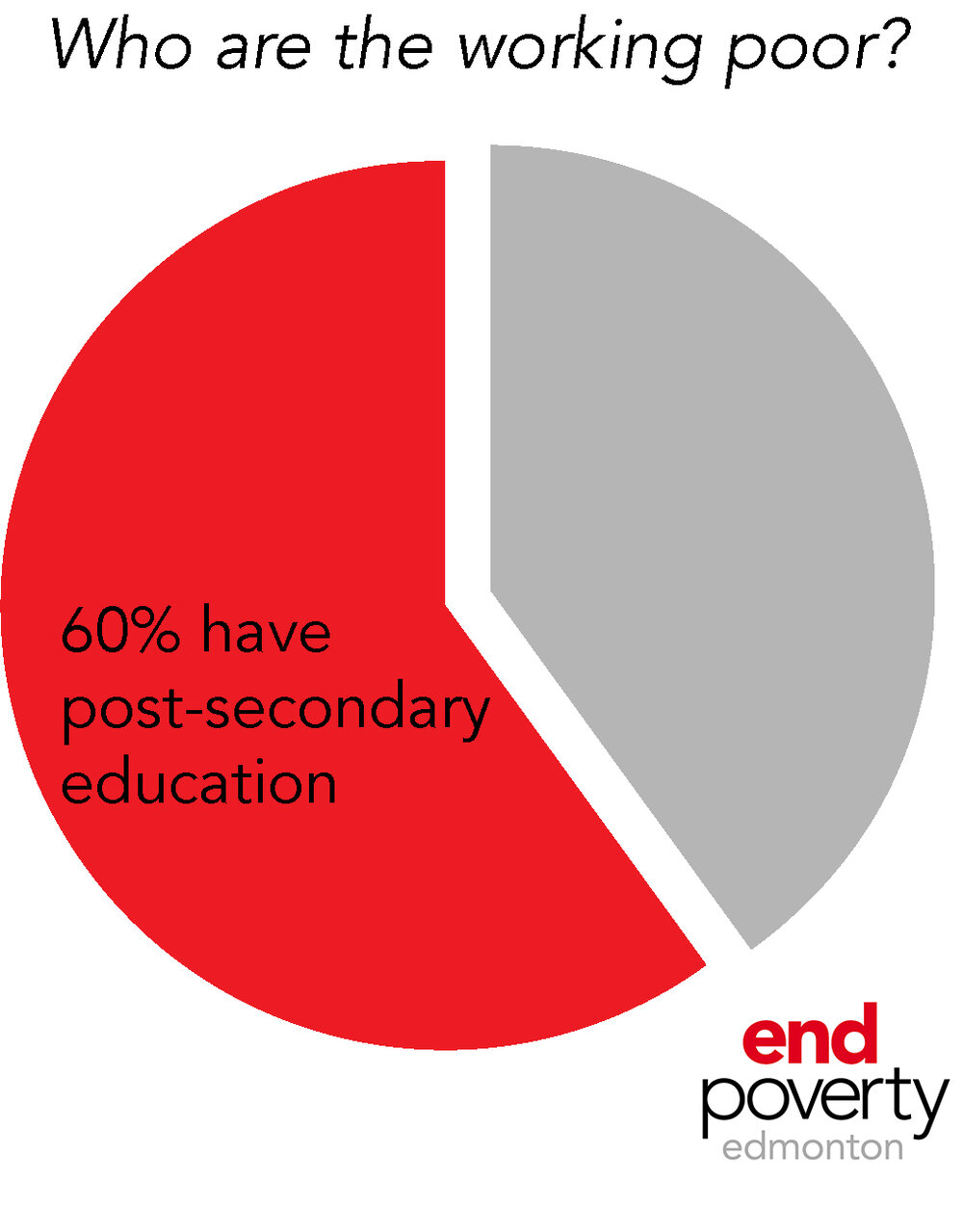

What we know is that the working poor are concentrated in younger age groups, particularly those aged 25-39. Unattached individuals, women, and immigrants are the most at risk for working poverty. The majority are full-time workers and in 2017, over 60% had post-secondary education. Overall, the general profile of someone in working poverty is a young and educated individual who invests a lot of time in the labour market.

Anyone Can Be Working Poor

That description sounds like many Canadians, meaning that anyone could find themselves in working poverty. Why is this happening when we persistently hear of skills shortages in so many industries? How do policy makers address these issues? Researchers have proposed several reasons ranging from increases in precarious employment to labour market discrimination. Although understanding the root causes of working poverty is important, in context to Canada's poverty elimination strategy, recognizing what support the working poor need is equally significant.

Support for the Working Poor is Limited

Examining Opportunity for All, many of the initiatives increase the resilience of the middle class and median household—the apparent theme of the strategy. Although government support for young, able-bodied, and unattached individuals is scarce; let's discuss one of the few available - the Canada Worker's Benefit (CWB). The CWB is a tax credit for low-income working households. Yet, the maximum annual amount for a beneficiary is only $1,381, excluding full-time students, and only those 19 years or older are eligible. As noted by Green, Kesselman, and Tedds in a 2020 report on UBI in British Columbia, there is a prevailing notion that an individual's value is tied to their ability to participate in the labour market. Yet, this perverse and antiquated notion disregards the different capabilities of each individual and the effect of precarious employment and other labour market frictions on the quality of jobs available. It is for these reasons, there are few systems and programs in place to support people in working poverty.

What steps do policy makers and civil society need to take to mitigate working poverty?

Afterall, we work to live, not live to work. It's about thriving, not surviving.

We need to be proactive in removing our own biases on how we link a person's work and value to society. Afterall, we work to live, not live to work. It's about thriving, not surviving. Perhaps a good jumping-off point is to restructure the current federal and provincial social assistance programs to be inclusive of prime working-age and childless individuals. For example, larger income supplements may be necessary for the working poor to meet food, health, and housing needs. Putting more research and consideration into universal basic income or living wages may also have potential. Overall, it's not just about putting money in the hands of the working poor. It's also about ensuring they have access to the resources and services some of us might take for granted.

Thriving is Hard When You're Working Poor

How can the working poor thrive when they have to spend more of their income on essential goods and services?

Sometimes we hear arguments like “they're not trying hard enough” or “they didn't study the right field.” How can a person save up money to pay for services or programs that could improve their prospects, when they are living paycheque to paycheque? How can the working poor thrive when they have to spend more of their income on essential goods and services? For example, the cost of insulin has been rising as more and more Canadians are diagnosed with diabetes. Think of it this way, the size of the pie remains the same; but the slices are cut smaller. Without imminent support, a working poor household needs to cut their budget somewhere to make room for other essentials. To build an inclusive and resilient economy, society and policy-makers need to abandon the archaic notion that working is enough to escape from, and protect against, poverty. It isn't and the data bears that out. When considering what policies are needed to support marginalized or disadvantaged groups, policy-makers should be mindful of the accessibility of such programs.Following our pie analogy, maybe the answer isn't to keep slimming the size of each slice - it's time to make the pie bigger.

So far we've focused on prime working-age individuals, but other groups also experience working poverty. However, there are already programs in place to support other high-risk groups. For example, the Canada Child Benefit, Early Learning and Child Care subsidies, various Housing programs, and even a higher grant-to-loan ratio for students exist. Assessing the impact of these programs in poverty elimination is a topic for a different day. What we want to emphasize are the inadequate systems in place to support the working poor.

Why focus on the working poor?

...the transition from working-age poverty to old-age poverty needs to be averted.

We're interested in prime working-age individuals because of the lack of support in a pivotal time in their lives. Recall that over 60% of the working poor have post-secondary education. Many of the working poor may have student loans to worry about, along with making ends meet for basic necessities. And it's no secret that humans are living longer lives. Thus, saving for retirement and worrying about making ends meet in old-age are other uncertainties faced by the working poor. It is for this reason that supporting younger age groups in poverty is to mitigate the negative socioeconomic outcomes associated with poverty across a lifetime. Otherwise, these issues will not only worsen their quality of life in the future, but potentially for a longer period in their old-age. That is, the transition from working-age poverty to old-age poverty needs to be averted. Even from an economic perspective, it would be more expensive for taxpayers in the future to fund larger healthcare expenditures. Obviously, support is needed now to avoid long-term negative effects in the future – for the individual and our society as a whole.

Where's this all going?

We've used the data to identify a neglected group in dire need of support, who are experiencing poverty. We've examined their realities and the systems reinforcing it. While we were quick to point out the flaws in Canada's social support system, we didn't discuss in detail any solutions.

Tune in next time when we dive into a strategy gaining further traction in the labour market — workforce development.