This is a guest post from our research collaborator: Alfredo Conde is a Research Assistant with the Community University Partnership at the University of Alberta School of Public Health, in his role he works closely with EndPovertyEdmonton. He has a Masters degree in Development Economics.

This is part II of a series he's written. Read part I here.

My previous post explored who the working poor are. From that research, we know that many people in poverty don't fall short in capability, rather in opportunity. As most people in working poverty have some sort of higher education, we have a pool of untapped potential. The personal investment in education has already been made, we just have to provide opportunities for its use. While there are few supports available to a large proportion of the working poor, there are programs, both available and possible, to get them out of poverty. First let's discuss the realities in today's labour market.

Opportunities for the working poor in today's labour market

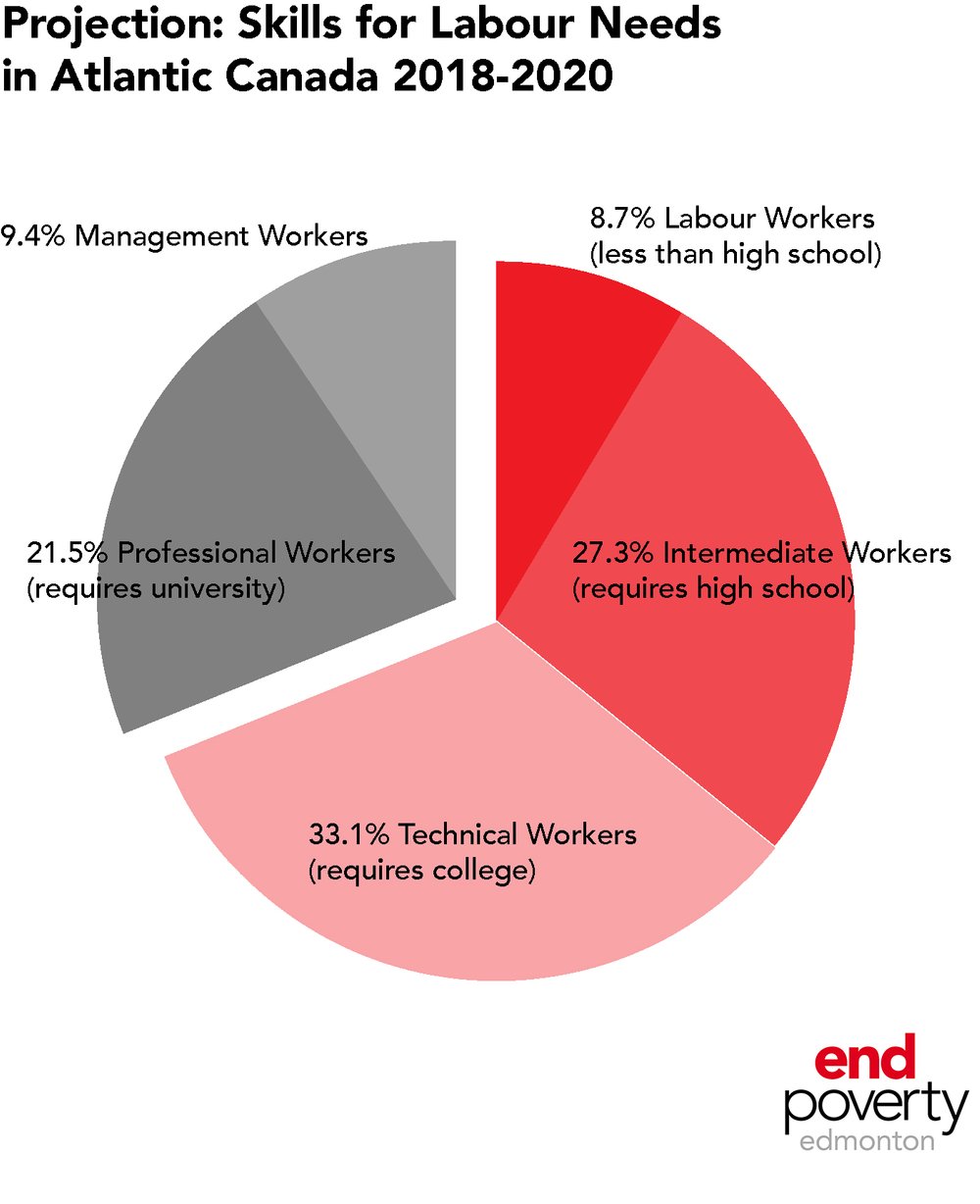

According to The Labour Market in Atlantic Canada, the majority of in-demand skills only require a high school diploma (27.3%) or non-university diploma (33.1%) in that region. In 2020 and 2021, among the most in-demand jobs in Canada are in skilled trades, which require either a high school diploma or college certificate or diploma at most. Yet, there appears to be a declining interest in trades, with many people opting for university degrees instead. Skilled trades appear to be struggling to attract new people, despite paying high salaries. Apparently, Canada's worker shortage problem is here to stay, and immigrants and other diverse groups appear to be the solution. They can help fill in the skills and labour shortages, especially in trades. But this “quick” fix is not without its issues.

Fixing an issue or compounding a problem?

Data reveals that a greater proportion of immigrants report that they need more skill training and education than Canadians by birth. Coincidentally, immigrants also have among the highest rates of higher education. Yet, many immigrants are not working in their field because their credentials are not recognized and many struggle to find work due to not having Canadian work experience. Therefore, work opportunities may be there, but immigrants face barriers to accessing them.

Skills are mismatched to the labour market

...native-born Canadians don't experience this growing competition, as they are generally preferred over immigrants

This tells us that immigrants in trades are potentially experiencing a skills mismatch. That is, their skills and education are not suited for their current positions. In fact, a study by Statistics Canada found that the supply of university educated workers has grown over the last 2 decades, but the supply of jobs requiring university education has lagged behind. Immigrants faced the greatest disadvantage as many arrive in Canada with university education. Yet, the growth in jobs immigrants fill are typically low to medium-skill, which means many immigrants are overqualified. Jobs that may be better matched to qualifications of immigrants are getting farther out of reach as competition between immigrants becomes more intense. Conversely, Statistics Canada also reports that native-born Canadians don't experience this growing competition, as they are generally preferred over immigrants. iPolitics notes that the immigrant-overqualification problem is more severe in Canada, than our southern neighbours, based on Statistics Canada data.

Women and antiquated work culture

...immigrants and people of colour, women struggle to remain in the industry due to the “macho” work culture, unequal pay, and lack of representation

Women are another group who can fill in labour and skills shortages in construction and other trades. Yet, we know that women face barriers to fulfilling employment. In construction, literature notes that along with immigrants and people of colour, women struggle to remain in the industry due to the “macho” work culture, unequal pay, and lack of representation in managerial positions. It is no surprise that these groups are more likely to leave their jobs due to dissatisfaction. Therefore, even in industries that need more talent, underrepresented groups face challenges to entering and remaining in the industry. Unfortunately, we know that underrepresented groups are overrepresented in working poverty. How can the talent available from people in working poverty be used to address skills and labour shortages? Let's discuss workforce development and look to B.C for some examples.

Coordinated workforce development can help

We need to understand and remove the barriers faced by the working poor...

Workforce development is a strategy in which the skills of the labour force are developed and nurtured so that workers have better access to jobs. One of the most well-known workforce development initiatives is the Canada-Alberta Job Grant (CAJG). In this program, the government covers 2/3 of the training cost of eligible employees up to $10,000 or $15,000 for unemployed people. What makes this program unique is that it helps remove a significant burden of the cost for an employer to upskill an employee. This could be very beneficial for employers who may not have the capacity to support their workers.

Despite the strengths of a program like the CAJG, it is not enough to support people in working poverty or connect them to the right jobs. Instead, a more direct approach to connecting workers with jobs may be necessary. We need to understand and remove the barriers faced by the working poor and other disadvantaged groups in accessing such programs. Workforce development has a huge potential in providing the working poor with the resources they need to get out of poverty as well as address skills and labour shortages. These programs can directly leverage the potential of the working poor and the needs of the labour market.

Let's make coordinated workforce development more effective

From Planning For The Workforce Of Tomorrow Through Collaboration And Strategic Partnerships, the City of Surrey identified opportunities for growth in the manufacturing sector engaging industry leaders. They found that the manufacturing and innovation economy in Surrey could grow by 134% in the next decade. However, manufacturers reported that they faced skill and labour shortages. Young workers and new graduates could bridge the skills gap through short-term training programs with post-secondary institutions (Simon Fraser University & Kwantlen Polytechnic University). The current workforce could be upskilled to increase the capacity for advanced manufacturing. In Workforce Development Partnership Reaching New Heights, Okanagan College and Kelowna Flightcraft Ltd. (KF) Aerospace anticipated a skills shortage in a niche field. By engaging the local labour market through promoting their technicians' program, they were able to keep their local economy stimulated. They promoted the aerospace technician program from Okanagan College and expanded the size of cohorts to meet the increasing demand from KF Aerospace. This partnership showed that engaging the local labour market to meet the demand instead of looking outwardly can keep the local economy innovative and prosperous.

What do these examples have in common and what do they mean for the working poor? First, it shows that industry leaders and educational institutions have the capability to turn a challenge into an opportunity. It shows that with the right strategy and leadership, workforce development can bridge the gap between job seekers and in-demand skills. Edmonton could use this approach to engage the working poor, mitigate poverty and facilitate access to good and sustainable jobs. However, such strategies also need to target vulnerable groups and dismantle barriers they face to accessing these resources. For example, language skills, recognizing credentials, diversity and inclusion initiatives, and pay inequality may also need to be addressed concurrently.

We have to work together

Workforce development and strategic leadership could be a panacea to Canada's worker shortage and the working poverty dilemma. Connecting people in working poverty to quality jobs will likely be a persistent challenge in policy making, especially with the advent of social procurement and community benefit agreements. Lessons learned from workforce development show us that a concerted effort is necessary to identify what skills are needed in the labour market, and provide people with the opportunity to obtain such skills.

We have to target working poverty

The cost of poverty in Alberta is estimated at $7.1-9.5 Billion annually in increased costs for healthcare, justice, and lost opportunity.

Due to the costs of leaving people in poverty on healthcare and other systems, people in working poverty should be the primary target for workforce development initiatives. In particular, immigrants, women and other diverse groups who are at the highest risk of working poverty, as they remain underrepresented in many industries and occupations.

So how do we fix Canada's looming labour and skills shortage? We need to increase the resilience of diverse and underrepresented groups, especially those overrepresented in working poverty, by providing them with opportunities to succeed in the labour market. Through collaborative action between industry representatives, policy makers, educational institutions, and other stakeholders, the working poor can be connected to in-demand skills and jobs.

Stay tuned to dive into topics such as “what is a good job and how do we know?” “what's an inclusive economy?” and other poverty-related things. In the meantime, hit us up if you'd like to talk more.